Herman, Sali (1898–1993)

Sali Herman (1898–1993), artist, was born on 12 February 1898 at Zurich, Switzerland, eleventh of eighteen children of Polish Jewish parents, Israel Hermann Yakubowitsch, drapery salesman, and his wife Sahra Mirlia, née Malinski. As a child Sali drew continuously, and he developed an interest in painting while still at school. His desire to become a painter was supported by one of his secondary teachers, but he had to abandon this ambition to help support the family by working in a glove shop, especially after his father’s death in 1914. Later that year, however, he and one of his brothers left for England. They stopped in Paris instead, where he spent nearly two years working odd jobs to earn a living, immersing himself in the cultural life of the city and mixing with artists, writers, and poets. There he discovered the art of Manet, Courbet, and Van Gogh, as well as the work of Utrillo and the Post-Impressionist painters, including Cezanne.

After returning home in 1916, Yakubowitsch studied life drawing and composition at the Zurich Technical School, and painting at the Max Reinhardt school. He first exhibited his work publicly in 1918 at the Kunsthaus Zurich. In 1920 his painting of one of his sisters, Yetta (1919), won him a Carnegie Corporation of New York grant of one thousand francs. He married Hannah Magnus in 1920 and worked full time as a dealer in oriental rugs, paintings, and other works of art. They separated in 1926, and on 25 August 1929 in Geneva he married French-born Paule (Paulette) Jeanne Marie Briand (d. 1973). He did not return to painting until about 1933. He had changed his surname to Hermann while completing compulsory military service (from 1918) in the Swiss Army with his six brothers; soon after emigrating to Australia the final ‘n’ would be dropped.

Leaving behind economic depression in Europe, rising anti-Semitism, and his frustration with the art-dealing industry, Hermann moved to Melbourne with his wife and the two children from his first marriage, arriving on 25 January 1937 to join his mother and several of his siblings, who had migrated there in 1920 to join his uncle. He studied briefly at the George Bell school (1937–38), which was then regarded as the centre of the modern art movement in Melbourne, and became involved in the modernists’ fight against (Sir) Robert Menzies’s proposed Royal Academy of Art.

Disillusioned with the politics of the art scene in Melbourne, and considering a return to Europe, Herman visited Sydney in 1938. He was immediately drawn to the beauty of the natural environment and the architecture and feel of many of the city’s buildings, and decided to remain. Association with artists such as Rah Fizelle, Grace Crowley, and Frank and Margel Hinder—all of whom also had experience of the world of international art—‘would have made him feel at home’ (Sali Herman Retrospective 1981, 8). He had an open and warm personality, and his circle of artist acquaintances grew: (Sir) William Dobell became a firm and lifelong friend, as did the art historian and critic Bernard Smith. In July he joined the Contemporary Art Society, which had Bell as its president, as a foundation member.

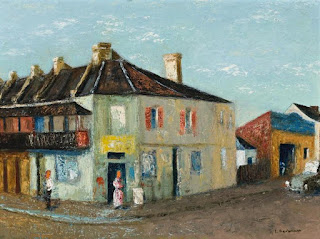

Herman soon came to be known for his paintings of the streets, buildings, and slums of the inner city, where, at Potts Point, he made his home. Finding inspiration in the urban environment, rather than the outback scenes and gum trees then popular among many artists and collectors, he developed a distinctive style within Australian art. He was actively discouraged, however, in his renditions of the dilapidated houses with their peeling paint and squalid look that detracted from the beauty of Sydney, including by the director of the National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Will Ashton. The choice of his McElhone Stairs as the winner of the 1944 Wynne prize was criticised in the Bulletin, the art critic of which compared the selection of a painting of one of Sydney’s ‘slummiest aspects’ to the awarding of the Archibald prize to Dobell for his portrait of Joshua Smith the year before (Bulletin 1945, 2). Herman maintained that artists must be true to themselves, and explained: ‘An old man or an old woman may not be attractive but may have beauty in their character. So it is with houses’ (Thomas 1962, 9).

Understating his age, Herman enlisted in the Citizen Military Forces on 22 July 1941 and transferred to the Australian Imperial Force twelve months later. He was employed as an instructor in camouflage with the School of Military Engineering’s fortress wing, Sydney, and with training units at Wagga Wagga, and in Victoria at Kapooka, until discharged in May 1944 with the rank of sergeant. In 1943 he had been naturalised. From May 1945 to April 1946 he was back in the AIF as a temporary captain and an official war artist, serving in New Guinea and on Bougainville. He based the twenty-six paintings he submitted to the Australian War Memorial on the many field sketches he had completed. Subjects included Japanese anti-aircraft guns stacked ready for surrender, road-building teams, camps, and soldiers burying the dead.

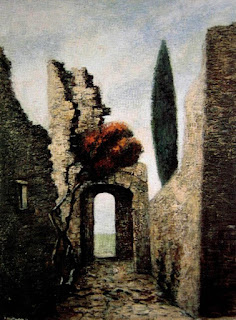

In 1946 Herman was awarded the Sulman prize for Natives Carrying Wounded Soldiers; he won it again two years later for The Drovers. He also won the Wynne prize three more times: in 1962 for The Devil’s Bridge, Rottnest; in 1965 for The Red House; and in 1967 for Ravenswood I. For many years he held regular one-man exhibitions around Australia, as well as participating in group shows. In 1953 he exhibited at Leicester Galleries in London, and in 1962 his work was included in an exhibition of Australian art at the Tate Gallery. He was appointed OBE in 1971 and CMG in 1982.

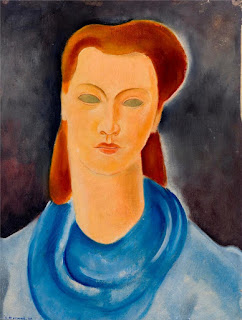

Over his career, Herman painted landscapes, still lifes, and portraits. He gave classes, judged prizes, travelled extensively around Australia and through Europe, presented lectures, and wrote critically and assertively on many subjects related to contemporary art. He became a mentor to many artists. He is best known for his purposeful and decisive handling of the palette knife on canvas, and for his distinctive use of colour to evoke an emotional impact. His paintings and vision inspired a generation to re-examine the heritage and artistic potential of the urban environment. In 1981, in the catalogue foreword to his major retrospective exhibition, the director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Edmund Capon, stated that: ‘His intimate, personal and evocative visions of what were once considered the backwaters of the city have become poignant statements on the march of progress’ (Sali Herman Retrospective 1981, 5).

A short man with ‘humorous eyes veiled with large horn-rimmed glasses’ and ‘his head circled with a halo of fuzzy white hair’ (Newton 1971, 2), Herman had a strong character, confidence, and personality. He was a lively conversationalist, generous with his time and money, and with a deep love of classical music and animals. He nurtured a love of art in his family: his son Edward (Ted) and his granddaughter Nada both became artists. From 1960 he had lived at Avalon, including in his later years with his son and daughter-in-law at their house Hy-Brasil—designed by the architect Alexander Stewart Jolly—where for a time the three artists worked in a family studio. In July 1979 in Copenhagen he had married New South Wales-born Wanda Maie Williams, an occupational therapist (d. 1982). Survived by one son and one daughter from his first marriage, he died on 3 April 1993 at Harbord and was cremated. His work is represented in major Australian public collections, including the AGNSW and the National Gallery of Australia.

No comments:

Post a Comment