Robby Müller was born on April 4, 1940 in Willemstad, Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles as Robert Müller. He is known for his work on Breaking the Waves (1996), Paris, Texas(1984) and Dead Man (1995). He died on July 3, 2018 in Amsterdam, Noord-Holland, Netherlands.

Trivia (6)

Member of the 'Official Competition' jury at the 41st Cannes International Film Festival in 1988.

Lives in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Jim Jarmusch at the Lincoln Center, New York, April 2014: "Robby Müller, I learned so much from this man about filmmaking, about a lot of things, about life in general and about light and about recording things and about capturing things in the moment and about trusting instincts. Robby and I had a really wonderful way of working: No storyboard, a shot list only if really necessary for ourselves. I still don't like making a shot list each day when I'm working. Robby's idea is about instincts, trusting your instinct and your intuition and Robby would always say things like: 'Of course we can plan everything in advance and when we go to that location it's a different time of day, the light is different, the clouds are different, so why would we cling to the idea we had previously? We must always be on our feet.' Think on your feet. And we did a lot of interesting things while scouting for this film together which was: We find the most dramatic, incredibly beautiful landscape you could imagine and then we would turn our backs on it and film the other way. [audience laughs] That was something that Robby said: 'Look how magnificent this is, we've seen it in a fucking calender! Let's look over there, it's a small tree and a rock, very sad and emotional, you know?' [audience laughs] So we would film that instead. And this is just one example of the kind of way that Robby thinks. And I learned so much from him, thinking that way. Don't look for the obvious, always keep your eyes open, keep thinking on your feet. Shooting a film is a process and you can't control everything in the process, so be open. Another thing Robby taught me was: O.K., you're shooting a scene outside and suddenly it starts raining. And most crews would say: 'Well, the scene doesn't take place in the rain, so let's pack up and we'll have to stop for today'. And Robby would be: 'I wonder what it would be like, if the scene's in the rain. Maybe it's much better'. Or if we already shot some of it: 'O.K. think of some dialogue where they say it's about the rain, you know?' Like, keep thinking, keep thinking, don't be set in your script. It's something that came from Nicholas Ray, who said: 'If you just gonna shoot the script then why bother?' And that's something Robby also instilled in me. Robby Müller is a kind of brilliant man who's a very rebellious teenager in part of his spirit and yet an incredibly technically gifted person.".

He was born in the colonial Dutch Antilles and didn't see Holland until he was 13 years old in 1953.

Lives with his family in a house with a view on the Prinsengracht in Amsterdam, Netherlands.[2008].

Made his reputation working with director Wim Wenders in Germany.

Personal Quotes (6)

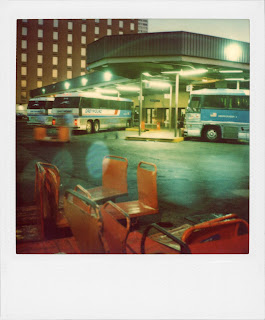

There are many films made today where the color is not really necessary, but you don't have a choice because the distributor wants color so he can sell it. But I always have a kind of 'thinking exercise' with the director, 'Why not in b&w?' or 'Why not in color?' So if we explain it to ourselves we know where we have to pay attention because, if you make the kind of films I generally make, color could give you too much information. Alice in the Cities (1974), for instance, would have been very bad in color. The same with Down by Law (1986). You would have had so much information around you that it would distract you from what you are telling. "Alice in den Städten" (1974) was originally planned for color. We even had a sponsor, Polaroid, who was bringing out that same year the SX-70 [a compact, reflex-viewing camera for Polaroid film] on a trial market in Florida and they agreed to sponsor us. But when Wim [director Wim Wenders] and I discussed it I said this will be no good in color; this little girl will be totally lost in this loud, exotic New York. Polaroid later agreed but they didn't withdraw their sponsorship. [June 1993]

For me, seeing 8½ (1963) was very important. What that cameraman [Gianni Di Venanzo] did there in a tunnel! Really breathtaking! You could totally understand the way he introduced Claudia Cardinale in that film. A fantastic moment. Nicely done. Carried by light. [2008]

In the early days - when I started my career - most cameramen were pretty arrogant. They didn't talk to you. I would have liked it so much to speak with them. But I never have! And now at Camerimage almost everyone you want to see or speak to is there. Storaro [Vittorio Storaro] - whoever - is there and you can speak to them if you want to. Yes, the feeling stays...teacher and student, actually I have always remained a student...like everyone. [2008]

I've not been involved with the later Dogma [Dogme 95] films, but I understand them very well, because that's the way I started. We had nothing. I was not frightened to shoot a complete film with one lamp. Or no light at all. As people dare to do it and take the consequences of it, they will find the light. [2008]

Wim [director Wim Wenders] and I became well known after The American Friend (1977) and I made features in Holland, Germany, France and a few - not many - in America. (...) When you're working there, there's not much room for improvisation and low-budget shooting. It's all well-planned in advance. It's all machinery...so at first you are overwhelmed by it and your work starts looking maybe 'American.' After my first film in Hollywood, I could have been booked out for a year, maintained myself there, got a Green Card, joined the union. But it's not really my world. [1993]

The absence of color can be a stronger factor than the presence of color. [2008]

*****

Robby Müller NSC, BVK, (4 April 1940 – 3 July 2018) was a Dutch cinematographer. Known for his use of natural light and minimalist imagery,[1][2] Müller first gained recognition for his contributions to West German cinemathrough his acclaimed collaborations with Wim Wenders.

Through the course of his career, he worked closely with directors Jim Jarmusch, Peter Bogdanovich, Barbet Schroeder, and Lars Von Trier, the latter with whom he pioneered the use of digital cinematography.[3] His work earned him numerous accolades and admiration from his peers.[4] He died on 3 July 2018, aged 78, having suffered from vascular dementia for several years.

Contents

Life and work[edit]

Müller was born in Curaçao (at the time in the Netherlands Antilles) in 1940, and moved to Amsterdam in 1953. He studied at the Netherlands Film Academy from 1962 to 1964.[5] He worked as cinematographer on a number of shorts before collaborating with Wim Wenders on his first feature, Summer in the City (1970). They went on to make many more films together such as Alice in the Cities (1974), Kings of the Road (1976), The American Friend (1977) and Paris, Texas (1984).

Apart from the movies with Wenders, Müller contributed to both mainstream US productions and independent films. His other work included the hazy, yellow-tinted cinematography of William Friedkin's To Live and Die in LA (1985), Sally Potter's The Tango Lesson (1997), Dom Rotheroe's My Brother Tom (2001), Lars von Trier's starkly shot films Breaking the Waves (1996) and Dancer in the Dark (2000), and Jim Jarmusch's gritty-looking films Down by Law (1986), Mystery Train (1989), Dead Man (1995) and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999).

He died on 3 July 2018 at the age of 78.[6]

On September 4, 2018, the movie Living the Light - Robby Müller premiered at the Venice Film Festival. This documentary by Claire Pijman is a visual essay about the life and work of Robby Müller. Pijman gained access to Müller's personal archive a few years ago and mixed it in a poetic way with his professional work.

Filmography[edit]

English-language films[edit]

Non English-language films[edit]

Awards and nominations[edit]

- 1975 & 1991 Deutscher Filmpreis, Best Cinematography

- 1984 Bavarian Film Award, Best Cinematography

- 1996 New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Cinematographer, for Breaking the Waves.

- 2009 Bert Haanstra Oeuvreprijs for his lifeworks.

- 2013 American Society of Cinematographers International Achievement Award for his lifeworks.

- 2016 Manaki Brothers Film Festival Golden Camera 300 for life achievement.[7]

No comments:

Post a Comment